This is the first post in a new series called Letterpress University. The series will cover basics on the history of letterpress, how it works, how to design for it, and how we work with our clients and designers. All from our own, rather unique perspective of course… Posts will show up about once a week (or whenever we have the time).

Once upon a time, there was a sleeping princess and a prince and a kiss that saved her and everyone lived happily ever after. But letterpress printing couldn’t be saved by anything as gentle as a kiss. Letterpress required a bite.

People will tell you that letterpress printing is the kind of printing that’s been around since Gutenberg printed his bible. And they’re right. Letterpress was how we humans started mass producing knowledge, and it was a doozy of an invention. It meant all those old monks who spent a lifetime getting just one copy of the Bible or St. Augustine’s Confessions all copied out and illuminated beautifully by hand could now spend that time doing other things, like say gardening and beekeeping, or caring for the sick and needy. But even more importantly, it meant that knowledge could spread and be shared like never before. Just downstairs in our personal library at Rowley Press, we have more books than a king could have acquired in a lifetime before good old letterpress came along. It’s a grand thing and as a devoted bibliophile, I’m extremely grateful for Gutenberg and all that refined the process after him.

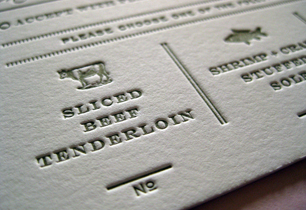

There is, however, a small difference you might notice in a book that was letterpressed 150 years ago or so and that letterpressed wedding announcement you keep adorning your fridge. All you have to do is run your finger across the page and you’ll feel that difference. It’s the difference between a bite and a kiss. The letterpress we all know and love today digs in to specialty paper and creates a tactile work of art that is valued for the deep bite it makes in the paper. A bite that would have made the good men (not many women printers back in the day, I’m afraid) that printed the first editions of Austen and Dickens and Goethe shudder. To them, an impression in the paper was just shoddy craftsmanship–crash printing they called it. The perfectly calibrated machine should be set so the finely inked type would touch the paper with just the lightest “kiss”, leaving the image but no impression behind. (Don’t worry, we’ll do a nice long, cozy post sometime on how this printing process actually manages to kiss and bite paper).

Fast forward to today. What changed? Why do we value and strive for a result that was the enemy of the good printer for hundreds of years? Well, it turns out there are other forms of printing that can “kiss” a piece of paper, or wood or rubber or metal or whatever else takes your fancy, a good deal more gently, efficiently, and clearly than letterpress printing can. Offset, lithography, laser, etc. Starting around the 19th C, letterpress machines were used less and less. By the end of the 20th C, they were all but obsolete. Fortunately for us, in the 1980s, people who liked the feel and craftsmanship of a hand run press started a revival. But they needed something special to set letterpressed work apart, to make it worth the time and effort (and cost) that printing by hand demanded. And thus was the beauty of the bite born.

Now, that’s not the whole story of the revival of letterpress. Lots of fun things helped it along, technologies and design programs and a mention in Martha Stewart Living in the early 90s (how can you not be famous after press like that?). But those are stories for another post, and they would have been meaningless if letterpress couldn’t give you a special product that no one else was. So be grateful for the bite my friends. And remember, sometimes a bite is better than a kiss.

Leave a Reply